Geopolitics and conspiracy: converging factors

At the crossroads of fantasy and manipulation, conspiracy theories have become a linchpin of international relations. From the burning of Rome to the secret laboratories of Ukraine, an exploration of the complex links between conspiracy narratives and global power games.

Conspiracy theories, long relegated to the margins of society, now occupy a central place in public debate. Amplified by social networks, magnified by high-profile political statements, they are becoming the tools of choice for manipulating opinion. Their proliferation is no mere accident of the digital age: states exploit these narratives to reinforce their geopolitical influence, destabilize their adversaries or control their own populations.

The “chicken or the egg” paradox is more a philosophical symbol than a biological paradox. Somewhere, sometime, a form of proto-chicken descended from the dinosaurs laid an egg from which a hen emerged. The question is more complex when it comes to conspiracy and geopolitics, when it comes to determining whether states began by bouncing off pre-existing theories, or whether they first created their own theories for propaganda purposes.

The astute reader will have understood that this question is merely a pretext for drawing up a short, perhaps salutary, inventory of the links between conspiracy theories and state informational maneuvers. As for determining which one pre-exists the other, this too will remain a philosophical question to be debated, since the definitions of the two concepts can vary from one fine mind to another.

The roots of evil

Conspiracy theories and informational interference don’t always overlap, but both concepts probably stretch their roots back to the dawn of humanity.

When it comes to “conspiracy theories”, i.e. theories that explain an event as mainly the result of a fantasized plot, historical examples are legion. The burning of Rome in the second half of July 64 AD? Rumours that it was caused by the emperor Nero quickly arose and continue to this day, despite the fact that the man was probably totally uninvolved.

Jews deliberately spreading the plague in Bavaria in 1319, or poisoning the wells of Western Europe in 1350? Fake news. The phenomenon was amplified during the French Revolution, with Barrel leading the way with his entire book dedicated to demonstrating that the Revolution was not a spontaneous movement, but the fruit of a grand conspiracy by philosophers and secret societies against the Catholic Church and the State. This was followed by centuries of “Judeo-something” fantasies – Judeo-Masonic, Judeo-Bolshevik… – right up to the fairly recent invention of a myth about the Khazars, an ancient people settled between the Black and Caspian Seas, which has been recuperated by various conspiracy communities around the globe. This overview would not be complete without mentioning a number of famous twentieth-century fantastical theories, including those about Hitler’s death, Kennedy’s death, the Roswell aliens, Diana’s death and 9/11.

When it comes to examples of informational warfare between states, history is just as rich. Long before the age of social networking or the modern press, governments were already seeking to shape perceptions abroad using tools suited to the times: rumors, secret diplomacy, and oral or written propaganda. It is striking to see the extent to which certain ancient writings resonate directly with modern geopolitical issues. Take, for example, the writings of Roman chroniclers who accused Carthage of ritual infanticide (a typical informational maneuver), an accusation still debated and rehashed in Tunisia since the 90s and the rewriting of teaching manuals on the subject. Likewise, most propaganda and informational maneuvers of the past were aimed more at the internal than the external: people tried to convince others within their own borders of the evil represented by others. This is how the French were able to publish great pamphlets to discredit England, or how the latter widely mythologized the power and origin of the invincible Armada. Then came the Cold War and the propaganda we all know, both within and beyond our borders.

Creating new conspiracy theories or amplifying existing ones: the Russian "model"

Operation Infektion is a well-documented model for the creation of a conspiracy theory by a state. Conducted by the KGB in the 1980s, this disinformation campaign aimed to convince the world that the AIDS virus was a biological weapon developed by the United States in a military laboratory. The KGB first targeted the media in non-aligned countries to launch the idea, then orchestrated amplification by third-party groups and influential individuals. This approach enabled the theory to reach a global audience and erode international confidence in American scientific and political institutions. A pattern of propagation that also illustrates how rumors can be reinforced by pre-existing biases, notably fear of biological weapons and distrust of the great powers.

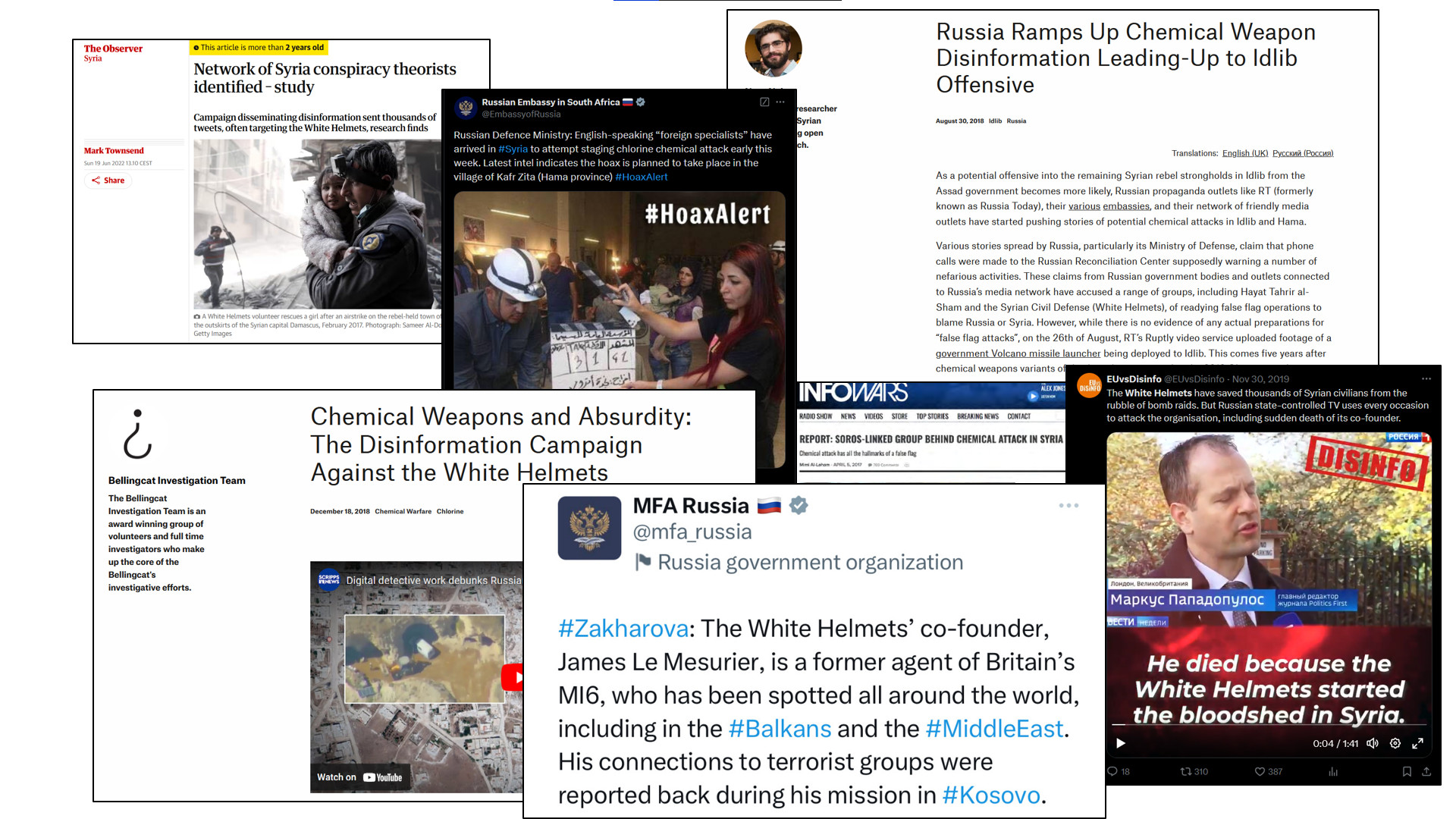

Since then, Russia has reiterated its position on several occasions, with mixed success, but it has done much to poison the public debate in a number of countries. It has done so in particular since the launch of its attempted invasion of Ukraine, by inventing the myth of American laboratories carrying out biological programs in Ukraine, or accusing the White Helmet of transporting chemical weapons to Syria in its ambulances. These theories were fabricated by the Russian services, but then took flight; no doubt traces of them will continue to be found here and there for a very long time to come.

In this same type of context, it’s not uncommon for states to find an interest in exploiting conspiracy theories already entrenched in certain societies. Once again, Russia is not to be outdone.

The chemtrail conspiracy theory, for example, has been exploited by Russian-affiliated media to fuel mistrust of Western governments. By disseminating articles and videos that amplify this theory, the strategy is to reinforce the perception that global elites are acting in the shadows to harm the population.

Another notable example is the use of vaccination theories. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia – again – spread stories insinuating that Western vaccines were dangerous or part of a global control plan. These messages targeted already skeptical groups, amplifying their fears and sowing confusion.

Russia is not alone

It would be a mistake to forget that other players are not hesitating to step into the breach. On the same themes, China has more than once been caught appropriating Russian disinformation campaigns about secret American laboratories in the Ukraine, or adding its own conspiracy banter about the origin of the Coronavirus, to blame Washington. And what can we say about Turkish President Erdogan, who “over the years has become a master in the art of fabricating conspiracy theories to keep himself in power”, or Azerbaijan, which tries to install the idea of a grand conspiracy by the French elites against the people, and feeds its narrative with all the lies that can contribute to it.

The manipulation of information is a phenomenon as old as humanity itself, and there is little doubt that examples of informational maneuvers carried out by social groups existed even before the invention of writing, although by definition no traces of them remain. The scale and sophistication of these maneuvers, like the installation and circulation of conspiracy theories, have reached new heights with each major informational technological evolution (printing, sound recording, image recording, internet, social networks, artificial intelligence). Our collective responsibility is twofold: on the one hand, we must each build a personal imperviousness to these poisons, and on the other, we must try at our own level to denounce, denounce and denounce again the methods of these autocracies that distill their poison in our Western societies. They do it to destroy us.

– H2V

If you have any feedback, don’t hesitate to find me on the Projet FOX Discord!